Indian audiences indeed got to watch “Sinners” — just not the way the rest of the world did. And one scene especially irked moviegoers.

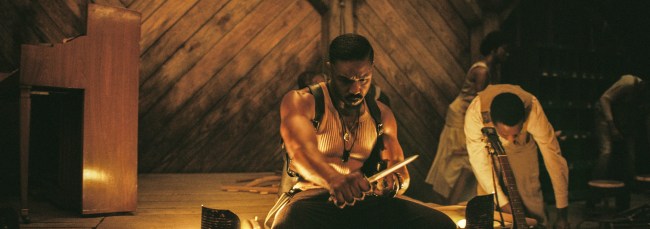

This hallucinatory sequence takes place at the midpoint inside Club Juke, when Sammie’s (Miles Caton) soul-stirring blues music becomes so transcendental that it conjures the spirits of the past and future. The guests rejoice, drinks in hand, while puffing on cigarettes. But in Indian cinemas, this immersive sequence gets interrupted — not by a vampire, but a certain disclaimer in an oversized font, stating, “Smoking and alcohol consumption are injurious to health.”

These health warnings are enforced by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), aka Censor Board, due to a government mandate. The statutory film certification body, under the Indian government, has the authority to suggest cuts and edits to movies before clearing a film for release. On scrutinizing the CBFC certificate available in the public domain, observant cinephiles even noticed that the film’s running time was almost two minutes longer than its original global version of 137 minutes in Indian theaters. And no, Indian audiences did not get to watch a director’s cut.

Again, the extra time is due to government-mandated graphic anti-smoking ads that play before the film begins and during the intermission (yes, all Hollywood movies in Indian theaters face a forced intermission). What makes this concern even more puzzling is that “Sinners” already carries an “adult” certificate in India, directly implying that children aren’t permitted. So, who exactly are the disclaimers targeting? Adults who could be influenced by Smoke and Stack’s (Michael B. Jordan) vices, if it weren’t for these jarring warnings?

Celebrated Indian filmmaker Anurag Kashyap (“Gangs of Wasseypur,” “Dev.D”) told IndieWire, “In a mood piece such as ‘Sinners,’ these disclaimers on smoking and drinking yank the audience out of the immersive experience that the filmmaker had painstakingly created, killing the mood and build-up in the process.”

Recent releases such as “Drop,” “Black Bag,” “Novocaine,” and “Warfare” have received similar treatment in Indian theaters. Nitin Datar, president of the Cinema Owners and Exhibitors Association, India (COEAI), said, “The guidelines, including the disclaimers, are mandated by the CBFC and are compulsory for the producers and directors to follow. Usually, it is the producers who insert such disclaimers, not exhibitors. These public service announcements (PSAs) are usually sourced from government agencies.”

At a time when global filmmakers are luring cinema-goers back into the theaters, amid massive competition from streaming platforms, is there a need to disrupt their experience by altering a director’s vision in the name of a government-regulated PSA?

Kashyap famously took India’s Censor Board to court when it demanded that these very disclaimers be embedded in his film “Ugly.” “I argued that it was a fundamental threat to artistic expression. The case dragged on, and, eventually, we had to abandon the fight and release it after our film got pirated. A filmmaker uses visuals, music, and nuance to create something for the audience to immerse in. And before they could even enter that world, a jarring ad ruins the experience,” Kashyap said.

Acclaimed actress and director Konkona Sen Sharma echoed a similar frustration. “There is often misogyny, sexism, crime, and violence (including violence against women) shown in films, which are far more problematic. Yet, we don’t see warnings that say, ‘Violence is injurious to health.’ We are burdened with disclaimers in films that already carry an ‘adult’ certification from the CBFC. Aren’t adults, who are legally allowed to vote, not equipped to handle fictional portrayals of characters smoking, without warnings flashed on screen?”

Sen Sharma is no stranger to the demands of the Censor Board, either. Even her critically lauded film “A Death in the Gunj” was subjected to cuts by the CBFC despite receiving an “adult” certificate, including a scene where a child merely picks up a cigarette and smells it. “I had already self-censored the scene during the writing phase. Originally, the child was supposed to pretend to smoke without actually lighting the cigarette, but I changed the scene to evade potential cuts. Such restrictions take away artistic nuance and strip away creative freedom,” said Sen Sharma.

Filmmaker Krishna D.K. (one half of the famous Raj & DK duo, plus films “The Family Man,” “Citadel: Honey Bunny”) noted that when a smoking warning pops up in Indian theaters during a key scene, your attention shifts. “I have seen the warnings appear even before the cigarette is visible. Over time, Indian audiences have gotten accustomed to it,” Krishna D.K. said.

However, over time, resistance to this kind of disruption has steadily faded. Kashyap puts it bluntly, “We’ve fought for reform, but nothing changes. Most producers and policymakers don’t care about aesthetics. Everyone, including the CBFC, is too scared of a potential outrage. What if someone takes offense, is a sentiment that lingers on.”

Sen Sharma, however, advocates for an age-based rating system rather than outright censorship, where the government gets to decide what the audience should and should not watch. She said, “If PSAs are crucial, a healthy compromise would be to show them at the beginning. List all the concerns (smoking, drinking, nudity) before the start of the film. After that, let the audience watch the movie without any distractions.” Mentioning how watching “Oppenheimer” with incessant “no smoking” disclaimers hindered his theatrical experience, Krishna D.K. echoes Sen Sharma’s views, adding, “Already, Indians are reading subtitles while watching foreign films; they do not need more text on screen to process.”

Journalist Aroon Deep, who closely tracks CBFC certifications, gave more context. “The alcohol warnings, however, are relatively recent and also speculative because there is no legal requirement for them to be inserted. The CBFC proactively added on its own accord. Indians, therefore, have to endure two layers of interruptions — one for tobacco and another for alcohol. And Hollywood movies such as ‘Sinners,’ ‘The Bikeriders,’ and ‘The Brutalist’ have had to face the wrath of it.”

Woody Allen famously refused to release “Blue Jasmine” in India over these disclaimers. Instead of complying, he preferred to skip India’s theatrical market entirely. Even the Oscar-winning “Anora” went straight to streaming. Krishna D.K. feels that skipping releases in a growing market such as India over such disclaimers may not make complete business sense, adding, “Every country has its share of cultural nuances, and filmmakers do make certain compromises. For example, a dubbed movie is not a direct representation of a director’s original intent; yet we accept it.”

“Sinners” isn’t the first film saddled with statutory warnings. Even the works of auteurs Martin Scorsese and Christopher Nolan have not been spared. In one of the world’s largest movie markets, even an unlit cigarette lying harmlessly on a coffee table could trigger a warning, forcing viewers to wonder if they paid to watch a Ryan Coogler film or a health lecture with popcorn.