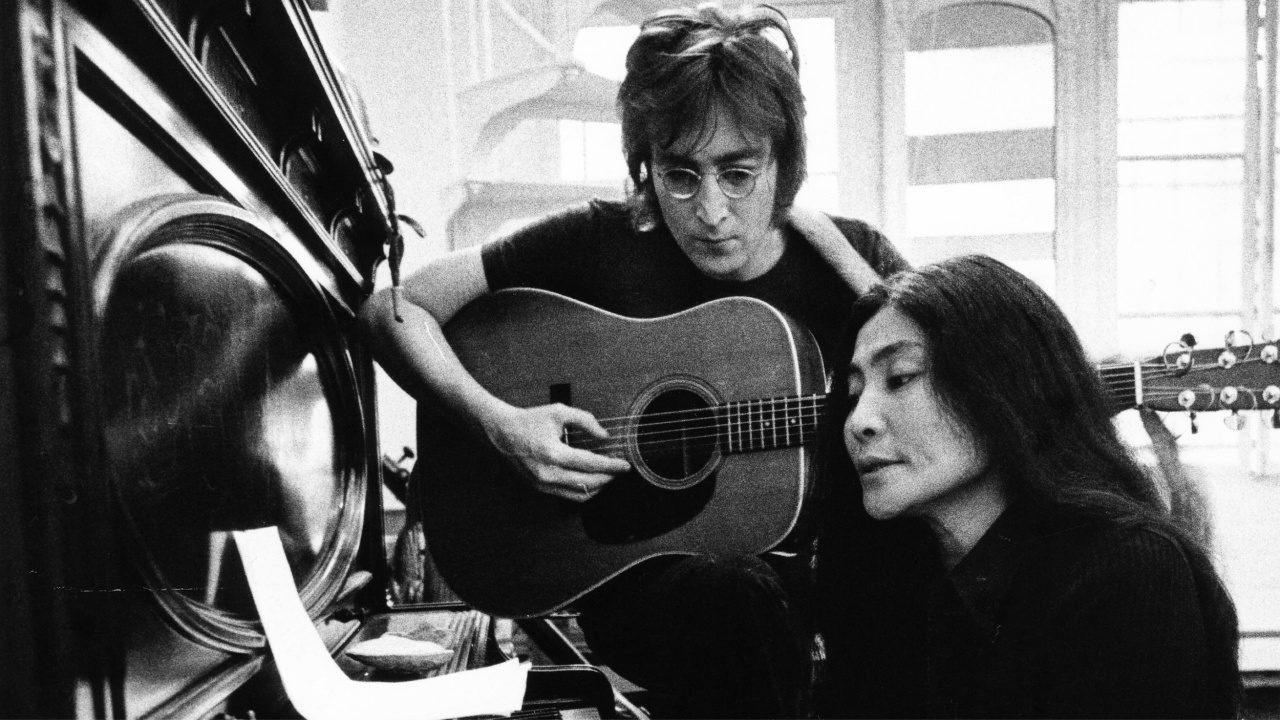

(L to R) John Lennon and Yoko Ono in the documentary ‘One to One: John & Yoko’. Photo: Magnolia Pictures.

Opening exclusively in IMAX theaters on April 11th before opening wider on April 18th is the new documentary ‘One to One: John & Yoko’, which focuses on John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s 18-month stay in Greenwich Village from 1971–1973, and leading up to their 1972 concert, “One to One”, which was the only full live concert that Lennon participated in after The Beatles broke up in 1970.

The film was directed by Kevin MacDonald (‘The Last King of Scotland’, ‘Marley’), and features never-before-seen footage from the “One to One” concert, with remastered audio overseen by Sean Ono Lennon.

Moviefone recently had the pleasure of speaking with filmmaker Kevin MacDonald about his work on ‘One to One: John & Yoko’, how he became involved with the project, creating a film around the footage, focusing on this specific point in John and Yoko’s lives and American history, their incredible relationship, the genius of Yoko Ono, and what John was looking for at that point in his life.

Related Article: Mary McCartney Talks Abbey Road Documentary ‘If These Walls Could Sing’

‘One to One: John & Yoko’ director Kevin MacDonald. Photo: Magnolia Pictures.

Moviefone: To begin with, can you talk about how you got involved with this project and your choice to focus on this specific time in John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s lives, as well as what was going on in America at that time?

Kevin MacDonald: Well, how this came to me is that the producer, Peter Worsley, had been chasing for years the rights to be able to use this concert. It’s a legendary concert, the only full-length concert that John ever gave after leaving The Beatles. So, it’s got incredible value, but it had always been swept under the carpet because it was so badly filmed and so badly recorded. So, the family didn’t really like it being out there because they felt like it didn’t represent John at his best. But with recent advances in sound technology, it sounds amazing, and it’s been remixed. We went back to the original negative of the film so we could improve everything. So, that became the core of the idea. It’s like he came to me and said, “Let’s make a film around that.” I’m a long time Beatles fan from when I was a kid, really. (John) was my first hero in pop culture, I suppose, when I was like 12 or 13, and then he died. So those things that meant a lot to you as a kid tend to be the things that are seared into you deep down. So, it is a lifelong dream to make something about him. But really there are three strands to the documentary. One is the musical strand, and that’s why it’s on IMAX. Because if you want to imagine what it was like to see John Lennon live, well this is your best opportunity to get close to that. The second strand is their personal life, what they’re going through. In this very brief period of about 15 months when they moved to New York from London, and they arrive in late ’71 until they move into the famous apartment in the Dakota building in New York in early ’73. So it is that time in this apartment where they’re living in a one room place with a huge bed and a big TV. They’re watching a lot of TV, and they’re mixing with all these radicals like Jerry Rubin and Allen Ginsberg, the poet, and all these people who are very activist and very progressive. They’re recording their own phone calls because they think the FBI are listening into them. So, they want to have their own record of what they’re saying. So, all the way through the film, you hear their intimate phone conversations. That’s the second strand. Then the third strand is what they’re watching on TV in their apartment, what I’m imagining they’re seeing on TV. So, it’s America in that period. So, you’ve got the whole lead up to Watergate, you’ve got the Vietnam War going on, you’ve got the Attica Prison riots, you’ve got also ‘The Mary Tyler Moore Show’ and ‘Bonanza’ and all these ads for Chevrolet. It’s like basically what TV would’ve been like for them that they’re seeing. What’s so remarkable, I didn’t set out to make a political film, but when you watch this film, you’re like, holy s**t. America is the same now as it was then. You have somebody running for president being shot live on camera, you have a black woman running for president, you have sit-ins on the campuses because of a foreign war. Then it was Vietnam, now it’s Gaza. It’s just endless the number of similarities and echoes with today. But I also wanted to make a film that worked as a movie, that’s kind of a different movie experience. It’s not like a documentary, it’s not like a drama. It’s something immersive, but hopefully also emotional and obviously musical. You’ve got this great concert at the heart of it.

MF: In addition to the concert footage, as you mentioned, the film also includes footage from TV shows, commercials, and news reports from that time. How did you decide what clips to use and how they would fit in the narrative of the film?

KM: Well, we watched a lot of stuff. I mean, a lot. Hundreds of hours of material. So, you’d go like “I wonder what was happening in foreign policy then?” You’d go and look at all the stories and then go, “None of it’s that interesting.” Or we started looking through news shows and every day, it seemed like in 1972 there was a hijacking. So, we thought, “Well, we have to put in a plane hijacking because they’re just everywhere.” Then you start looking. “Who are the people who are doing the hijacking? Oh, it’s the Black Panthers or some offshoot of the Black Panthers.” So, you go down these wormholes and we tried to relate what was happening in John and Yoko’s life to what’s happening in what you’re seeing in the archive, but also relate it to the songs. So, there’s obviously a sequence which is about Vietnam and about the war and the horrors of the war and why they’re so active in trying to bring peace. We decided to set this footage as quite in your face footage of the war against ‘Instant Karma’, one of John’s great solo songs. Which is counterintuitive because Karma is not obviously a song about warfare or whatever, but it is a counterpoint that really is fun. Each one, the song makes you look at the footage differently and the footage makes you look at the song differently. Then there’s examples where, for instance, when we’re talking about John’s own personal life. He’s talking about how he has a huge chip on his shoulder, and trauma over his childhood. Not being brought up by his mother and father, and how his mother was killed almost in front of him by a drunken policeman driving too fast one night when he was 15. Then we go to ‘Mother’, the song that he wrote about his mother and how he felt abandoned. It’s one of the most moving parts of the film. So yeah, the personal and the political are intertwined in it.

(L to R) John Lennon and Yoko Ono in the documentary ‘One to One: John & Yoko’. Photo: Magnolia Pictures.

MF: Everyone knows that John Lennon was a genius, but Yoko Ono may be the most maligned and misunderstood person in pop culture over the last 60 years. However, I walked away from this film realizing that Yoko was a genius too, and the driving force behind John’s solo music and activism. Did you walk away from this project with a newfound respect for Yoko Ono as well?

KM: 100%. The more I saw of John and Yoko together, the more I realized how deep their love for each other was, but also their respect for each other. And how deeply John respected her, not just as a person, as a lover, but as an artist and how influential she was on him. I mean, for instance, it’s not in the film, but he has said elsewhere that ‘Imagine’, maybe his most famous song, she basically wrote the lyrics. They’re based on the poetry that she wrote in a book called ‘Grapefruit’, and he put the melody to it. So, they were sort of joined at the hip. I think what you realize is that when you look at the story of this period of the breakup of The Beatles and everything. From her point of view, not from his point of view, not from the fan’s point of view, you realize how difficult it was for her. She experienced a lot of racism, and she talks about it in the film. People had voodoo dolls that they stuck pins in of her, and it made her develop a stutter. She lost all her confidence and she had, I think two or three miscarriages at this period because of the pressure on her. You begin to then see her when she’s singing, and she’s singing from these incredible gutsy performances, these wailing songs which are so ahead of their time. It’s like punk, it’s like Johnny Rotten (Sex Pistols) singing or something like that. You see that she was his equal and maybe in some ways his inspiration.

MF: During the moment in time that the movie covers, John was really trying to distance himself from The Beatles legacy. Can you talk about his mindset at that time and what he was trying to accomplish both personally and professionally?

KM: He arrives in New York and one of the things we have at the beginning of the film is a radio recording in which has got John and Yoko and people are saying, “Welcome to New York.” They’ve obviously only been there for a day or two. John says, “I’m here because I want to move on from The Beatles”, effectively. “I want to be me now,” he says. That’s sort of the feeling you get through the film, is that here’s someone who has been one of the most famous people in the world, in the greatest rock band of all time, but he’s trying to find out “Who am I now? I’ve been through this tumult of fame and everything, but who am I and what should I do now with my life?” He’s only 31 years old. But he’s had this whole legendary career, and he is trying to figure out what do I do next? Who am I? I think that in one way you can see the whole movie as being an answer to that question. Of him struggling to figure out who am I? What do I do?

(L to R) Yoko Ono and John Lennon in the documentary ‘One to One: John & Yoko’. Photo: Magnolia Pictures.

MF: Finally, to follow up on that, do you think John eventually figured that out before his passing in 1980?

KM: I think he finally did. I think that in the years after our movie covers, he had basically a nervous breakdown. He split with Yoko, he went and had what’s called “The Lost Weekend” in LA where he got drunk for a year and a half every day and played music with Harry Nilsson and people. Then it made him miserable. I think he did have a nervous breakdown. I think partly because of all the effort they put in politically in the period we’re covering here, trying to get Nixon defeated, and then they failed miserably. They totally failed. He had to question the whole idea of maybe you can only do small things to change the world. You can raise money in the benefit concert, which is at the heart of this film, for Disabled kids. “I can do that. I can make their lives better. I can do these small things, but I’m not a politician. I’m going to concentrate on the things around me I can control.” I think that in the last period of his life, I think there was a contentment. He had a son, Sean Lennon, and he was basically a house husband. He looked after Sean a lot and still made some music, but he was very reclusive and very quiet. I think he found some sort of peace and some sort of harmony.

“A war of love and transformation.”

Showtimes & Tickets

An exploration of the seminal and transformative 18 months that one of music’s most famous couples — John Lennon and Yoko Ono — spent living in Greenwich Village,… Read the Plot

What is ‘One to One: John & Yoko’ about?

The film is centered around concert footage and audio from Lennon and Ono’s “One to One” benefit concert held at Madison Square Garden in August 1972 on behalf of children at the Willowbrook institution in Staten Island. The “One to One” benefit concerts were the only performances which Lennon performed following The Beatles’ split in 1970. The film also follows the trajectory of their 18-month stay in a Greenwich Village apartment from 1971–1973.

Who is featured in ‘One to One: John & Yoko’?

(L to R) Yoko Ono and John Lennon in the documentary ‘One to One: John & Yoko’. Photo: Magnolia Pictures.