“Drop Dead City” falls into a category of documentary I think of as wonkish but gripping. Produced and directed by Peter Yost and Michael Rohatyn, the film is about the financial cataclysm that hit New York City in 1975, when the powers that be figured out that the city was $6 billion in debt. There was no money to pay anyone: firefighters, cops, teachers, sanitation workers. The city walked right up to the edge of bankruptcy. (That’s not an overstatement.) Had New York City been anything but New York City — had it been a business, a family, or even another city — it likely would have declared bankruptcy. But after a prolonged logistical-ideological war about what to do, the city was deemed too big to fail (even though it had failed, and to a shocking degree).

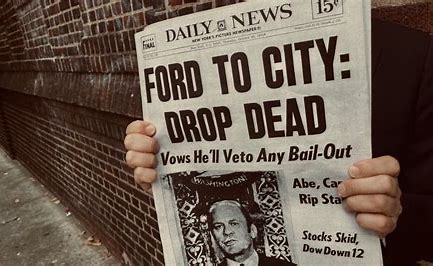

The film’s title refers to the infamous New York Daily News headline that ran on Oct. 30, 1975 (“Ford to City: Drop Dead”). President Gerald R. Ford never actually said those words, but the headline appeared after representatives of New York went to Washington to meet with the Ford administration. They asked for a federal bailout and were given the cold shoulder. There were complicated reasons for that (Ford’s chief advisers, Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, were two of the reasons). But it was that headline, 50 years ago, that stamped New York’s financial crisis with the imprimatur of legend.

The reason I call “Drop Dead City” wonkish is that the film isn’t a seamy urban-cultural biography; it really is about the money. And the more that the movie follows the money, the more that it tells a story larger than New York — a story with direct application to today.

In the mid-to-late ’70s, when New York was sunk into the torpor of potential economic ruin, the city was fabled in another way. This was the period of CBGB and Summer of Sam, when New York was famously squalid and dangerous, when whole sections of it had a bombed-out vibe of neglect. Yet in all that crumbling concrete, there were stray weeds and flowers — the artists and thrill-seekers who grooved on the funk and the fear. It became part of the mythology of the ’70s that New York City was a wreck, but a fabulous wreck, an exposed nerve of a city, a sordid nexus of desperation and creativity where to exist there was to plug into the life force. Yet for too many people who weren’t middle-class bohemians, the city had become hell. It was hell and it was a life force. (Just listen to Lou Reed’s “Dirty Boulevard.”)

“Drop Dead City” shows us bits and pieces of that story, but it’s really about the economic engine that was so rusted it had come to a standstill. And you can feel the malaise in the fluorescent bureaucratic tone of the film’s archival footage, which is dominated by politicians and bankers and city officials. Seen now, this is a saga of bad ties, bad shirts, bad haircuts, bad sideburns, and bad lighting: the New York caught by the Sidney Lumet of “Serpico” and “Dog Day Afternoon.” And the real thing is even uglier. Yet that’s part of the drama — the sight of all these government squares putting their earnest, bean-counting heads together to pull the city out of the abyss.

So why did New York nearly become a disaster area?

There was a level of fiscal irresponsibility that had gone for too many years: records stuffed into a thousand different drawers, and as for the bookkeeping…well, there was none. There were no books.

Yet financial chaos needn’t equal Armageddon. The real problem, and it’s one that “Drop Dead City” places front and center yet never totally deals with the implications of, is that New York City was a generous, overflowing bastion of the liberal dream. The unions had extraordinary power, and the city’s workers were notably well-paid, with job security and pensions. More than that, the city offered a wealth of services to the poor and the middle class. New York was the Ur melting pot, a city of immigrants that incarnated a densely packed East Coast version of the American Dream. New York was so liberal that even a Republican mayor, like John V. Lindsay, was, in spirit, a Democrat. The city didn’t believe in less government. It believed in however much government it took to help its citizens succeed.

That’s what had gone on for years, to the tune of the city spending much more money than it took in. And it all came to a head when Abe Beame was elected mayor. He was a tough, dry nut who spoke like a bulldog and stood at 5’2”, but he knew, from his time as comptroller, what a wretched state the city’s finances were in, and he wanted to clean them up. After recruiting the new comptroller, Harrison J. Goldin, to do an audit (Goldin is interviewed extensively in the film), the bad news came out: The city was up to the tips of its skyscrapers in debt.

What ensued was an orgy of finger-pointing and budget slashing. It was Beame’s fault! No, it was the fault of the unions! The first thing Beame did was to cut construction projects (Battery Park City, the 2nd Ave. subway line), leaving construction workers high and dry. (This would have turned Archie Bunker into a Trumper.) And when the city began to lay off vast swaths of its workers (2,000 sanitation workers, 2,300 firefighters, 15,000 teachers), up to and including police officers (5,000 of them), who had never before been laid off in the history of the city, those workers reacted with a collective disbelief and outrage. How could they do this? The garbage piled up. The crime statistics spiked.

But there was no money to pay anyone.

“Drop Dead City” charts how those pivotal months of 1975, from the spring through November, when a deal was ultimately struck, unfolded like a thriller. Would New York fall off a cliff? The city had already borrowed its way into oblivion. The answer couldn’t simply be…more borrowing. Beame formed a task force, the Municipal Assistance Corporation, known as Big MAC, which would try to refinance the city’s debt. Big MAC was headed by the investment banker Felix G. Rohatyn, who according to the documentary proved a master politician. That one of the film’s co-directors is Rohatyn’s son, Michael Rohatyn, might throw that conclusion into doubt. Yet I don’t think it’s wrong. Felix Rohatyn was deft at bringing the different sides together, and at recognizing what was needed: a financial solution in which everyone — the unions, the state, the federal government — had skin in the game.

“Drop Dead City” captures how there was a staggering contradiction at the heart of New York City in the middle of the 20th century. It was going to help its workers and residents, even if it couldn’t afford to do so. That sounds noble but raises the issue: How is that sustainable? And there’s a way that the documentary doesn’t actually want to go there. Gerald Ford never said “drop dead,” but he did give New York the brush-off — until he didn’t. The federal government came around. So did the teachers union, led by the tough nut Al Shankman, who went down to the wire refusing to offer the teachers’ pension fund as a way to cover the city’s bond payments — until he changed his mind. In a sense, what went on was a high-stakes game of chicken.

Yet there was an ideological war burbling underneath, all revolving around the question of what government exists to do. “Drop Dead City” suggests that Gerald Ford lost the presidential election of 1976 because he was on the wrong side of that equation. New York’s electoral votes put Jimmy Carter over the top; the film says that Ford’s reprimand of New York cost him the presidency.

In hindsight, though, Jimmy Carter’s presidency looks more and more like an anomaly. Ronald Reagan was elected four years later, on the promise of less government, and you don’t have to be a higher mathematician to draw the line from Reagan’s slashing of government to Elon Musk’s chainsaw. (Reagan romantics like David Brooks of the New York Times will tell you that those are two different things; but that’s part of the “Never Trump!” conservative delusion.) “Drop Dead City” captures how New York fell into a hole of its own devising, then made an essential correction. But it’s not like this was simply a matter of bad bookkeeping. What New York’s fiscal crisis revealed, for maybe the first time, was a crack in the liberal dream.